Imagine standing on the summit of the world’s largest dormant volcano and giving a cultural demonstration that holds your audience captive with tales of old Hawaii.

Or, imagine lacing up your hiking boots to trek into a national park to plant rare, gorgeous flora. Envision, too, admiring endangered species in their native homes. Picture being surrounded by an island forest of eucalyptus and pine trees as you work towards protecting one of the planet’s most delicate and magnificent environments–all the while golden sand beaches await your footprints ten thousand feet below.

Friends of Haleakala

Whether you call it responsible travel or volunteerism, there’s no doubt that doing charitable work at home and on vacation provides a terrific sense of community, gratitude and accomplishment.

Visiting Maui and interested in giving back to the island? Consider devoting a slice of your time to volunteering at Haleakala National Park.

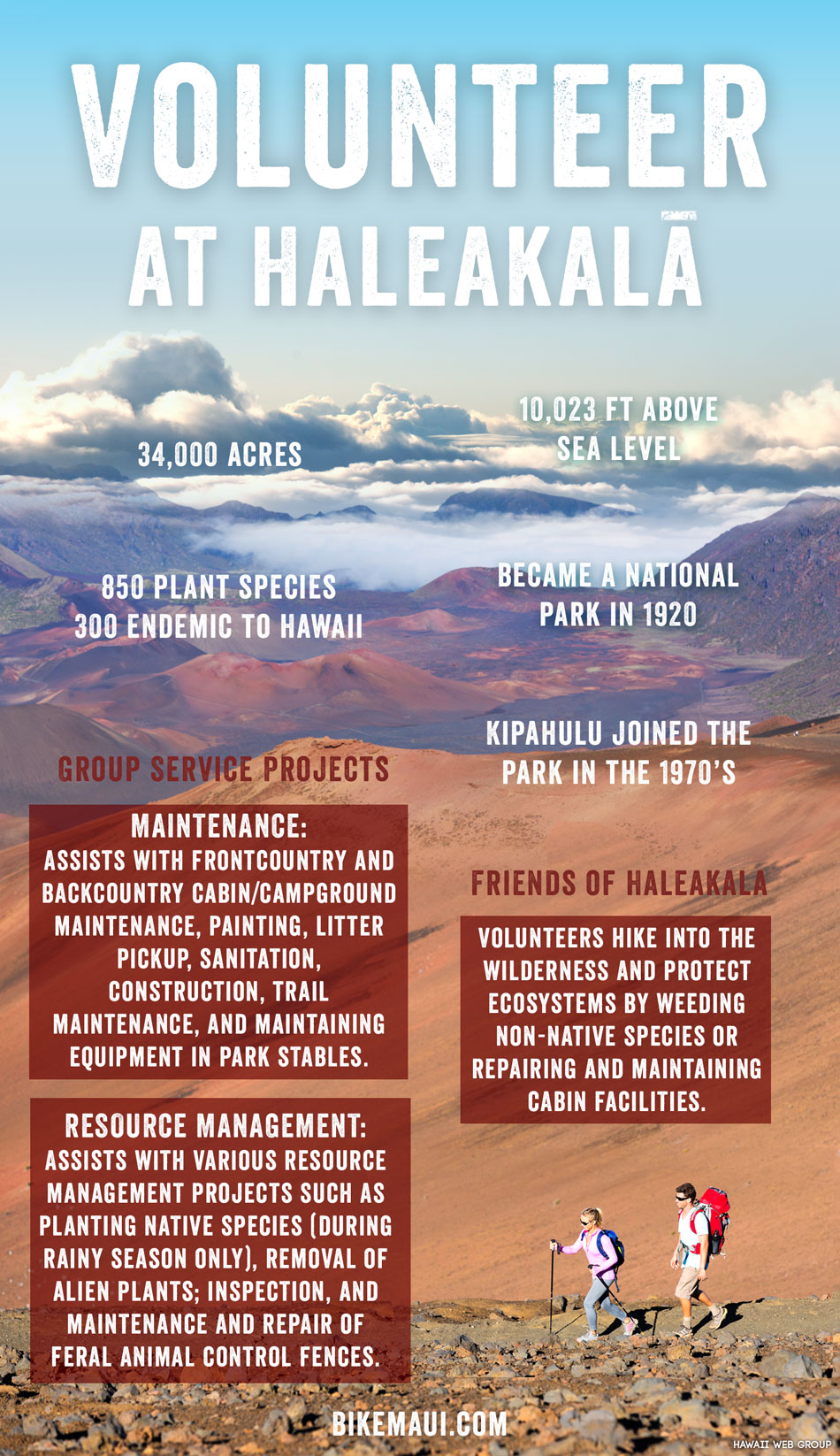

Often referred to as the House of the Sun, or wao akua—a temple of the gods—Mount Haleakala is the crown jewel of the Valley Isle, soaring towards the heavens at 10,023 feet above sea level.

Comprising nearly 34,000 acres that span from cinder desert and lush rainforest to pure, unadulterated wilderness, Haleakala was designated a national park in the early 1920s.

Since its appointment into the system—an endeavor helmed by President Thomas Jefferson and described by writer Wallace Stegner as “the best idea America ever had”—Haleakala’s preservation has been put into meaningful and careful place.

Take the Haleakala Silversword, for example—a stunning succulent and relative of the sunflower that grows nowhere else on the planet. Prior to Haleakala’s appointment as a national park, the unusual plant faced extinction; since then, it’s moved in status from endangered to threatened, with its record low of 4,000 plants surging to 65,000 in the decades that followed.

Part of the park’s success—and the conservation of its native flora and fauna—is due to the volunteers who generously donate their time and energy.

In 2014 alone, compassionate locals and visitors contributed nearly 23,000 hours to the park’s protection, upkeep and operation, while it’s estimated that the value of the volunteer workforce in parks across the country exceeds $91 million annually. But consider thistle eradication and keeping lighthouses burning a small price to pay to bask in Earth’s stunning natural beauty.

Whether you’re on Maui for a brief stay or would like to support the iconic destination from a remote position in Connecticut, Haleakala National Park offers volunteers a range of assignments and activities.

Selection is based on each volunteer’s special set of skills, with a wide variety of choices to appeal to many:

A budding builder or seasoned construction worker? Demonstrate your talents by signing up to build fences, paint buildings, maintain trails, and participate in other hands-on projects. Are you a natural when it comes to public speaking and customer service? Short talks, guided tours, and other forms of imparting the park’s marvelous history are available. Tend towards the quieter side? Express your interest in helping to maintain the park’s library and assist with historic park documentation. Aspiring ornithologist? The park brims with extraordinary birds, from the Nene goose—the official state bird of Hawaii—to the Hawaiian Petrel, or ‘ua’u, an endangered, star-navigating seabird whose last known nesting colony is found at Haleakala’s acme. And for those who live three thousand miles away or more: rest assured that you too can contribute by enlisting as a virtual volunteer.

For those so swept away by Maui’s splendor that they’ll be staying for half a year or longer, volunteer opportunities are also available for more extensive periods.

One of the most exciting among them is the chance to serve as a trail guardian through the pilot program, Kia ‘i Ala Hele—a popular position, selected by application, that requires six hours per week for a minimum of six months. In this role, with spots in both Kipahulu and on the summit, volunteers educate guests about wilderness ethics, the park’s impressive resources, and the NPS’s Leave No Trace codes—a series of principles designed to keep Mother Nature as she was made, from leaving rocks, plants, and objects where you find them to concentrating on preexisting trails to avoid further impact. Additionally, Kia ‘i ala Hele volunteers instruct hikers and campers on the shield volcano’s natural and cultural history, giving visitors in an in-depth look at its emergence from the ocean floor more than a million years ago to its evolution as the 10th most prominent peak in the nation.

Those volunteering in the district of Kipahulu are in for a serious treat.

The valley was named part of the park in the 1970s and remains one of the most restricted natural regions in the entire nationwide park system. Here, volunteers will gain a vast appreciation for the fabled and breathtaking region of Hana, where striking views of its famed waterfalls compete for attention with the dramatic, jagged coastline.

Volunteers who descend several miles to the crater floor will be placed in a realm like no other on Earth.

Far-flung and uncommonly quiet, this is the eerie, mesmerizing heart of Haleakala’s magic—a place so isolated it prompted author Jack London to remark, “…why are we the only ones enjoying this incomparable grandeur?” The floor—which is technically an erosional depression shaped by the merging of two valleys—is home to the park’s three cabins, which thrive in part on volunteer maintenance. With overnight trips to remove invasive species and work on the lodgings, volunteer camping excursions take helpers deep into parts of the caldera that are otherwise off-limits to visitors. And who could argue with the sweeping moonscapes and one-of-a-kind stargazing?

But perhaps the greatest gift of volunteering at Haleakala rests in the knowledge that efforts are going towards safeguarding the park’s beguiling beauty and fragile ecosystem.

To note: while 850 plant species are found within the park’s parameters, only 300 are endemic to Hawaii. Left unchecked, Friends of Haleakala National Park President Matt Wordeman says, and “invasive plants will dominate the landscape and force out native plants, insects, and animals”–just in case you need another reason to start dusting off that backpack. What’s more, service trips are punctuated with lessons in Hawaiian lore, island culture and the world of astronomy. Indeed, these volunteer excursions are so rich and rewarding it wouldn’t come as a suprise for you to say the pleasure is all mine.

Mahalo, I am excited to learn that I may be able to volunteer at my very favorite place on earth, Mt. Haleakala.