Perennially blue skies, eighty-degree temps, surf warmer than bathwater—is it any wonder that Hawaii is thought to have some of the finest weather in the world?

But on the island of Maui, a wholly different kind of weather occurs within Haleakala Crater—while the volcano itself has a tremendous, even radical impact on the Valley Isle’s overall climate.

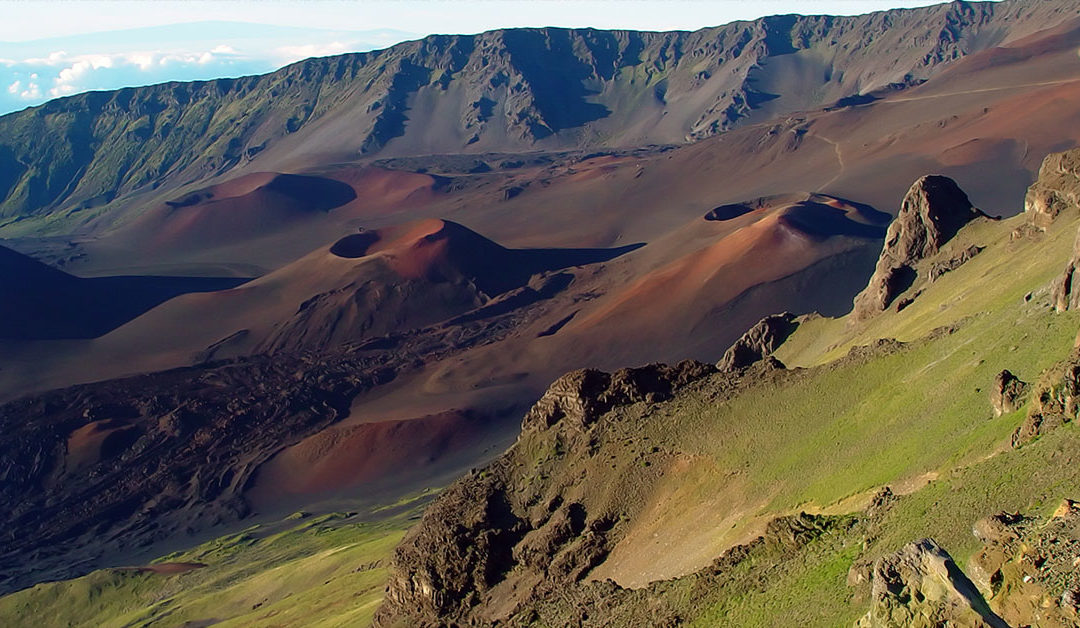

Haleakala hovers over the entirety of the island like a paragon of power, luring visitors to its moonscape summit and dramatic vistas of the outlying islands.

Here, however, the balmy temperatures that are enjoyed on the leeward sides of the island—Wailea, Kihei, Lahaina, Ka’anapali—seem to belong to a universe apart.

And in a way, this is true.

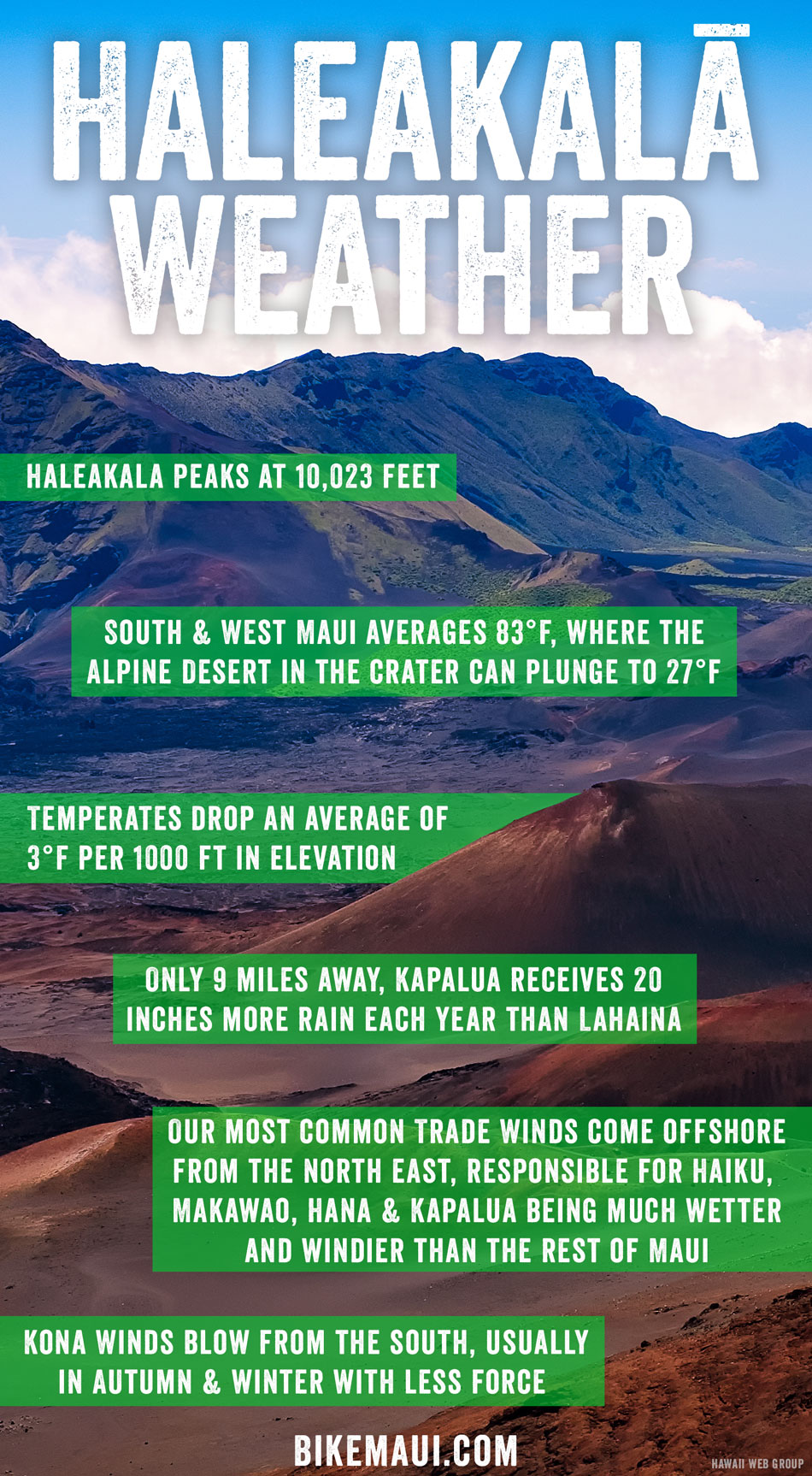

While the lower regions of the island enjoy a warmer environment (the average on the tourist-heavy south and west sides is 83 degrees), the greater Haleakala National Park, which comprises over 30,000 acres, is home to a vast array of sub-climates—most notably the alpine desert that’s found within the volcanic crater. Here, time seems to stretch towards infinity, sound is poignantly acute, and temperatures plunge to as low as 27 degrees. And while the average temperature at the visiting center may be between 41 and 62 degrees, couple in wind chill and you have an altered image of the bright ambiance one readily associates with the islands of Hawaii.

Much of Haleakala’s weather is due to the shield volcano’s sheer elevation: Towering 10,023 feet above sea level, it also renders Haleakala a shield in more ways than one—as well as something of a wind funnel.

Those sultry island breezes for which Hawaii is known are far more than just a way to rock a hammock between two palms. Indeed, of all the weather systems to impact a mass of land, Hawaii is most vulnerable to wind.

In essence, wind is the flow of air molecules. Consisting of nitrogen, oxygen, water vapor, and other trace elements, air molecules travel swiftly. Where those winds originate from—and which part of the island they drive into first—has an enormous force on whether one will be sailing on a smooth sea or cowering from sand blasts on the beach.

For much of the year, Maui experiences trade winds—gales that arrive from the northeast quadrant offshore. Due to its form and position within the Pacific—imagine, if you will, Maui split in two at the top of its “head,” wherein the left half is the leeward side, while the right is the windward flank—those northeasterly winds run into the “port” side of the island and turn the areas of Haiku, Makawao, Hana, and Kapalua wetter and windier than the hotter, dryer towns of Kihei and Lahaina. And that demarcation is vital: Kapalua, for example, receives 20 more inches of rain per year than Lahaina (even though it’s only nine miles away), while Hana is prone to frequent showers.

The second type of wind Maui confronts is what’s commonly called Kona winds. Blowing from the south—keep in mind that the Big Island, which is home to Kona, rests south of Maui—these winds tend to fall during autumn and winter, and are often lighter than the trades that dominate Maui’s weather for 80% of the year.

Whether arriving from the south or the northeast quadrant, these winds collide with whatever obstructs their path. This means that the winds that hit the islands have traveled across huge stretches of open ocean—the Aloha State is roughly 2,400 miles away from any continental land mass, making it the remotest population center on the planet—only to suddenly strike the soaring volcanoes that shaped the archipelago.

When wind strikes Maui’s two tallest peaks—first and foremost, Haleakala, followed by Pu’u Kukui (or the West Maui Mountains)—it splits and travels on either side of the mountain, much in the way that the flow of water cleaves when it confronts a rock in a river. To think of this on a more fundamental level—as in how this might impact you on your vacation—consider the “corridor” that is Central Maui. Lying flat on the isthmus between the two volcanoes, this is one of the breeziest regions of the island, while the leeward sides rest in a zone of weaker winds in what’s known as a “wind wake.” This is a boon for residents of and visitors to these parts, who are essentially protected from the northeasterly winds by Haleakala. Likewise, the sunnier shores of Lahaina and Kaanapali are partially sheltered by Pu’u Kukui, while Kapulua—which sits, exposed, on the northern tip of the island—is subjected to northeasterly wind and rains, and is defined by its lushness and cooler clime.

What’s more, the wind barrier that is Haleakala (as well as Pu’u Kukui) causes the air that moves by to be orographically lifted. In short, this pushes the air at lower elevations to loftier parts. As it ascends, the air cools, heightens in humidity, and can lead to precipitation, thus explaining why Makawao, at nearly 1,600 feet and on the windward side of the island, is one of the dampest areas of the Valley Isle.

The weather on Haleakala itself, however, tells a wildly different story.

As that mass of air climbs up Haleakala, it thins significantly. This isn’t quite as mysterious as one might think. Air is compressible—meaning, it’s denser at sea level because the ocean of air above it presses down; the higher one (or a mountain) ascends, the less pressure it has to contend with from above. And the thinner the air, the weaker it is in molecules like oxygen, water vapor, and trace elements, which ultimately gives the upper regions of Haleakala chilly, even sub-Arctic temps and a noticeably parched quality to the air. In fact, the air here is so dry that any clouds that make it past certain elevations tend to evaporate rapidly; from the beach towns below, one can look up at Haleakala and note the band of clouds that seem to ring the volcano like a halo.

Additionally, the zenith of Haleakala exists above the inversion layer of the Earth’s atmosphere, which in turn creates a temperature inversion, wherein temperatures increase rather than decrease with height. This translates to cooler temperatures at 7,000 feet than at the very top of Haleakala, while the basin of the crater, which dips below its highest peaks, presents a colder climate (and leads hotel concierges to urge visitors to bring a jacket when going “upcountry” to view one of Haleakala’s world-renowned sunrises).

Additionally, the zenith of Haleakala exists above the inversion layer of the Earth’s atmosphere, which in turn creates a temperature inversion, wherein temperatures increase rather than decrease with height. This translates to cooler temperatures at 7,000 feet than at the very top of Haleakala, while the basin of the crater, which dips below its highest peaks, presents a colder climate (and leads hotel concierges to urge visitors to bring a jacket when going “upcountry” to view one of Haleakala’s world-renowned sunrises).

Whether you elect to drive to Haleakala at dusk or bike down its slopes at dawn, chances are you’ll be astounded by the varying climates in which you’ll find yourself, in part because the temperature drops an average of 3 degrees for every 1,000 feet in height.

And with that will no doubt arrive a greater appreciation for Maui’s range and grandeur. Perennially blue skies may be in abundance around the island, but so are patterns of weather that are nothing short of divine.

Haleakala Photography courtesy of Maui Photographers Organization.

Haleakala. A wonderful and awe inspiring place to visit, The jewel in a never to be forgotten holiday.

Have been to the summit many times. Hiked the crater a few times. It’s an awesome, magical place. Not able to do it anymore, and I miss it!

Only been there once the sunrise was amazing, the ring of fire is something to see.